We need to talk about national security

We need to discuss national security. Since the release of the National Defence Strategy in April 2024, much has been written and said about the need for a national security strategy. However, it doesn’t start with a defence strategy; it begins with a national conversation about the interconnected domestic and regional economic, social, and sector challenges facing Australia. These challenges influence our lives, thoughts, and actions to build resilience.

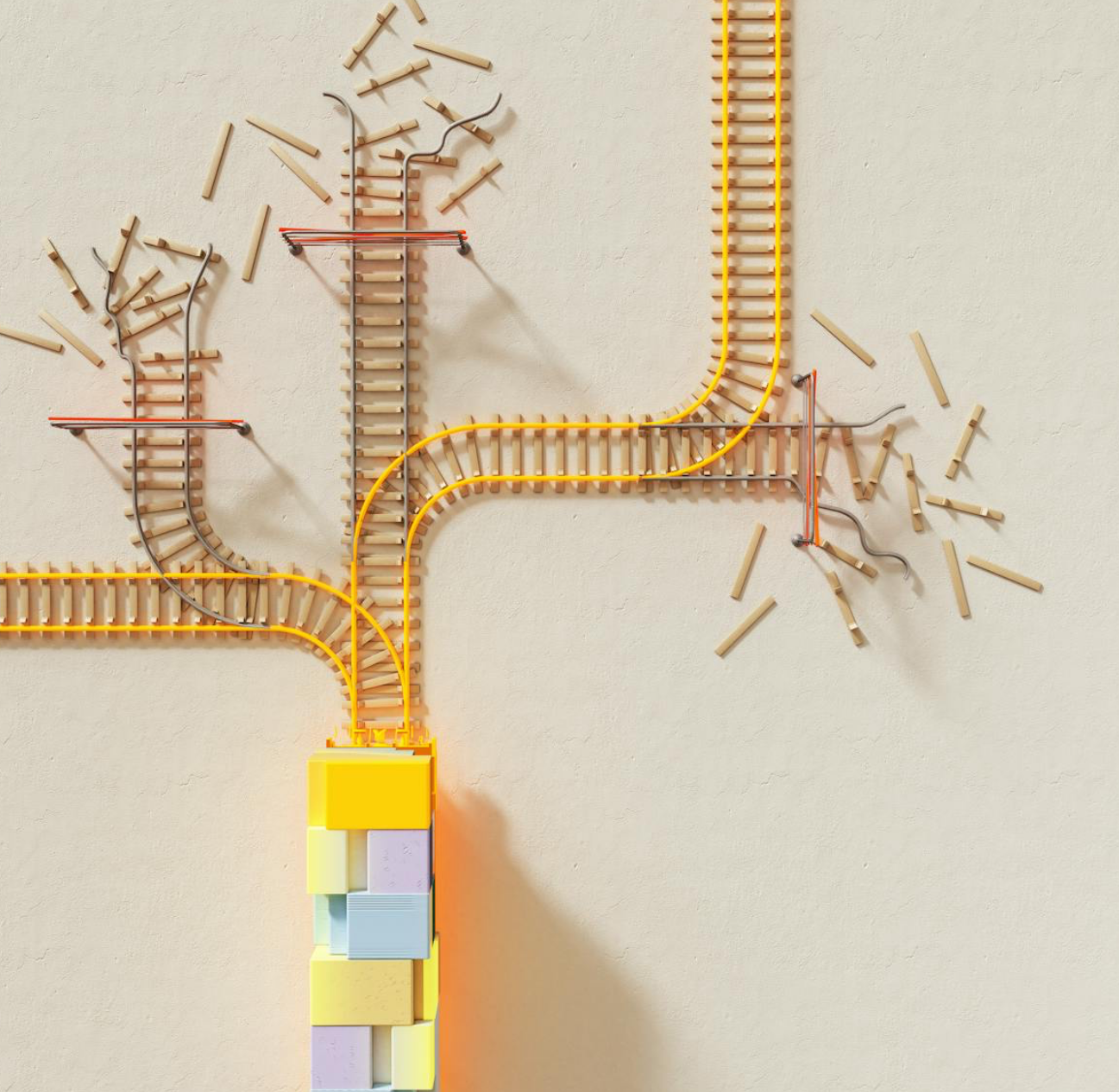

The first thing we often overlook when pursuing national strategies and ‘whole of nation’ approaches is that they require multi-sector, cross-government, and wider community engagement. By their nature, they are complex and require a commitment to engage and, most importantly, a commitment to listen. And of course, a strategy is of little value if it is not acted upon quickly.

Wider engagement broadens the scope, scale, and complexity of any strategy. Engagement also takes time and raises expectations among stakeholders, who become increasingly reluctant to engage when their views are not valued. However, wider engagement can also deliver a much improved result.

In recent years, there has been a tendency to label federal government strategies as ‘national.’ This might be reasonable in a military or defence context, but even then, there are wider interests to consider that often do not get a look in. While this highlights the difficulty of engaging widely and meaningfully to develop locally relevant responses, it is beyond unhelpful.

Critically, we need to think about national strategies in terms of the ‘sum of the parts.’ Across the Australian community, there are a range of interests that can, and will, contribute willingly rather than being forced to if something goes wrong.

During Covid, we saw individuals, communities, governments, and industry step up because it was important for the nation. Communities did not need a national strategy to tell them what to do; they needed national leadership, which is a completely different thing.

So, getting back to calls for a national security strategy, it is not as simple as it sounds. If ‘national’ means a federal strategy that details the brief references in the National Defence Strategy relating to ‘international affairs’ and ‘resilience and preparedness,’ that would be beneficial and provide federal agencies with important guidance and framing that is currently lacking. However, if ‘national’ is to be truly ‘whole of nation,’ then that is a much broader and all-encompassing endeavour. Such an approach has much more complexity and requires genuine and meaningful involvement by many more stakeholders.

A holistic national security strategy should enhance and leverage foundational social and economic infrastructure. We also need to remember that credibility is based on both asking the question and doing something with the answer. And sometimes we forget that strategy needs to be implemented and usually requires funding.

A wider approach and meaningful engagement starts with a national conversation at all levels, featuring ‘plain speaking’ about the multitude of complex challenges Australia is facing.

While this may be the intent, a genuine approach to engage meaningfully across most issues is currently missing the mark. We consistently hear this through evidence presented during national inquiries and royal commissions, such as those on aged care, natural disasters, veterans’ suicide, and domestic violence.

Covid showed us that issues highlighted through prior reviews were very real. It also confirmed research and inquiries over many years that there were pre-existing challenges with aged care, public housing, urban isolation, mental health, supply chain dependence, and so on. It highlighted that our foundational social and economic infrastructure was lacking.

Many have spent their time analysing what went wrong during Covid, but it is not about that. It is more about what we should have done before Covid when we had the chance. In the case of Covid, we should have listened to sectoral experts, including epidemiologists, who had been warning us for years that a pandemic was likely. If we had acted on the pre-2020 recommendations of many inquiries and reviews, the impact of the pandemic would have been less severe.

Change is needed. We need to shift the focus from crisis response to ensuring our foundational social and economic infrastructure is robust enough to withstand major and concurrent disruptions of any kind, irrespective of the cause. A national security strategy assumes that the only national impact would come from war in our region, but that is old thinking and oversimplifies the complex, interconnected, and inequitable world in which we live.

There is plenty of advice for those interested and who know where to look about alignment and consistency of national security advice. This highlights another key issue: the advice is not easily accessible or understood by a wider audience. Military references to ‘asymmetric capabilities’ and ‘impactful projection’ have little meaning for wider audiences. It is not so much about consistency of national security advice; it is more about the clarity of that advice and what we need others in the community – individuals, communities, industries, etc. – to do with the advice.

This equally applies to national response frameworks should conflict arise in the Indo-Pacific. The national frameworks that do exist focus on government responding or acting. However, despite the focus on preparedness and resilience, we are yet to engage in a national conversation on why we need to respond, what it means for communities, regions, organisations, and importantly, what they will choose to contribute.

Discussion about establishing the ‘social licence’ misses the point because that does exist. Australians are concerned about what is happening in our world, but we see those concerns play out in issue-specific protests and confused and oversimplified proposed solutions. We need to ensure citizens understand where we are sitting in terms of the interconnection of these challenges, the escalation triggers, and what contribution we all might need to make, today and tomorrow.

There is growing distrust in information systems as well as the delivery and interpretation of information. This is an issue in the security and prosperity context as it is for all other sectors. The ease and speed of spreading misinformation and disinformation is something we should all be concerned about and actively address.

Governments are rightly focused on social media platforms and groups that deliberately engage with misinformation and disinformation, particularly when they promote extremist agendas. However, those with extreme agendas are merely tapping into a deeper sense of distrust and confusion prevalent across the wider community.

Local communities are taking the lead in preparing for climate extremes and severe events, but clearly, the widening economic divide within our community, the changing climate, and instability in our region represent a devastating level of disruption. We have lost the art of speaking plainly, but we also need to spend more time listening.

In the absence of a national conversation, we will continue to mislabel strategies in this area and miss the opportunity to leverage the sum of the parts that the Australian community can, and is willing to, contribute.